In this episode, I’ll discuss how to evaluate drug interactions.

The Hospital Pharmacy Academy is a place for pharmacists and pharmacy residents to gain practical clinical pharmacy knowledge and skills. Inside the Academy, you will find monthly video-based Masterclasses, weekly literature digests, and members-only forums to connect with other pharmacists and get answers to your hospital pharmacy questions.

For a limited time you can get a 2 day trial of the Academy at pharmacyjoe.com/trial.

Context

The ideal response to a potential drug interaction depends very much on the context of the level of care the patient is receiving.

For example, in episode 112 I discussed the combination of linezolid and fentanyl and the risk of serotonin syndrome. In an ICU setting with intense patient monitoring, this combination is acceptable. My tolerance for risk of the linezolid-fentanyl interaction changes outside of critical care settings. Monitoring is less intense with a higher nurse to patient ratio on a general medical unit or in an ambulatory setting. Additionally, alternatives to either medication are much easier to find outside of the ICU.

Third party drug interaction services are often of little to no use in determining the clinical significance of a potential drug interaction. Whether it is fear of being sued or some other reason, many references overstate the risk of potential drug interactions and water down their service with drug interactions of minimal risk.

Classification

Authors Philip Hansten and John Horn published in 2001 an operational classification system for classifying drug interactions (ORCA). They describe 5 different classification levels for drug interactions based on risk vs benefit and the action that must be taken.

Class 1 – There is no situation where the benefit outweighs the risk (such as pseudoephedrine plus a monoamineoxidase inhibitor).

Class 2 – Avoid use unless there is no alternative or the interaction is desired (such as warfarin plus aspirin).

Class 3 – An increased risk exists but monitoring may be an acceptable course of action (such as low doses of fluconazole with 3A4 substrates).

Class 4 – Minimal risk.

Class 5 – No interaction.

Hansten and Horn publish annually a guide to the Top 100 Drug Interactions using in part the ORCA system. The 2017 version of this guide was just released. While the guide now contains far more than 100 potential drug interactions, the authors do a superb job focusing on only the clinically relevant interactions that are class 1, 2, or 3. I have been using this book in my daily practice for over 10 years to weed out the clinically insignificant drug interactions.

Predicting pharmacokinetic drug interactions in the absence of known data

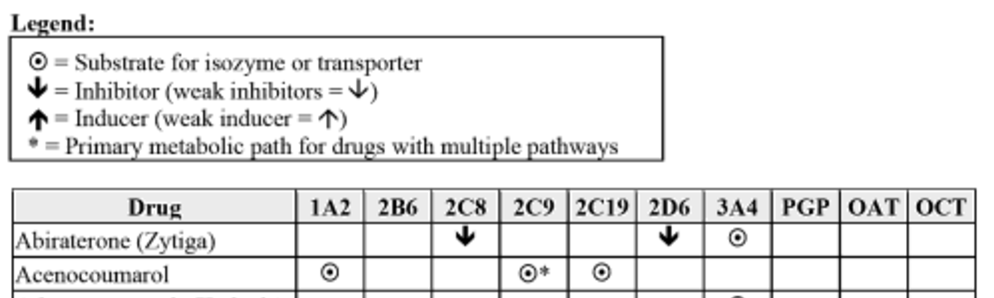

Not all drug interactions are known, and new drugs arrive on the market with limited drug interaction data. To allow clinicians to predict pharmacokinetic drug interactions in unstudied combinations, Hansten and Horn also publish an extensive listing of medications that affect and are affected by the cytochrome P450 system, as well as other transporters such as p-glycoprotein:

This chart allows clinicians to identify interactions between enzyme inhibitors, inducers, and substrates. In addition, if a medication has a primary pathway of elimination, it is identified in the chart. This extra piece of information can be used to hypothesize on the degree to which an interaction may be significant. For example, although amitriptyline is metabolized by 1A2, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4, and PGP, the primary pathway of elimination is 2D6. Using this information a clinician may choose to allow the use of a 3A4 inhibitor with amitriptyline with the knowledge that many other pathways for elimination exist.

Hansten and Horn’s Top 100 Drug Interactions also contains guidance for antibiotic interactions with warfarin, interactions with herbal products, as well as genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome p450 enzymes.

QTc Interactions

The best section of Top 100 Drug Interactions has to do with evaluating QTc drug interactions. My method for evaluating QTc interactions draws strongly from Hansten and Horn’s book and I discuss it extensively in episode 12.

I highly suggest if you have not already read episode 12 about QTc drug interactions that you take a moment to do so. In brief, two things I keep in mind about QTc drug interactions are:

1. Be risk averse whenever possible. Take for example a patient with no allergies on sotalol prescribed levofloxacin for CAP. As long as their renal function is good this is a low risk interaction that I could just monitor. But ceftriaxone plus doxycycline is just as good for CAP and completely avoids the risk of torsades. Why would I take the risk when I have another 1st line treatment that doesn’t include the torsades risk? Things get murkier when you are having to decide between using a 2nd line drug or monitoring the interaction. Take the same patient but give them anaphylaxis to penicillin. Would vancomycin plus aztreonam plus doxycycline provide the best cure for their pneumonia? How do I balance the added risk of toxicity that using vancomycin brings? Sticking with the levofloxacin and monitoring the patient in the hospital might be more reasonable here, and this brings me to my 2nd point.

2. ECGs are cheap and non-invasive. You should have no hesitation asking for one if the purpose is to evaluate or monitor a QTc drug interaction. Literally, the cost to the hospital is the ink and paper – the machine and technician salary have been paid for already and this fixed cost doesn’t enter into the equation.

If you like this post, check out my book – A Pharmacist’s Guide to Inpatient Medical Emergencies: How to respond to code blue, rapid response calls, and other medical emergencies.

Leave a Reply